Well, it is while since my last post. Over the last 4 weeks I have delivered three papers in three different countries. So – I thought I would give an overview of them here.

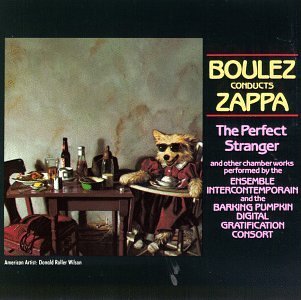

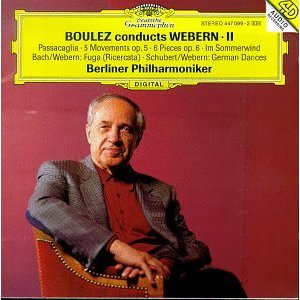

The first was a paper entitled ‘The Impossible Made Real: A Typology of Loops and an exploration of the impact of immediacy and hypermediacy in Popular Music’. It was delivered at the University of Leige in early March with my colleague Dr Ben Challis. This was followed by a conference at the University of Edinburgh entitled ‘ Live Music In Wales: interim findings of a research project financed by the Welsh Assembly Government’, followed by a paper this week at the University of Valencia, focusing on Frank Zappa and Gesture. What follows is a synopsis of what we covered in the first conference in Leige, and this will be followed by details of the paper in Scotland later. I covered the content of the paper in Valencia in an earlier post.

We are currently developing the concepts of the loop paper into a book chapter – so watch this space!

Firstly – to see some of the video content we discussed on the day via a Prezi, look at this link.

Secondly – here is an overview of what was discussed!

The Impossible Made Real: A Typology of Loops and an exploration of the impact of immediacy and hypermediacy in Popular Music. Slide 1

Dr Paul Carr and Dr Ben Challis

Glamorgan University

We would like to open this paper by agreeing with Richard Middleton’s perspective that ‘all popular songs, to a greater or lesser extent, fall under the power of repetition’ (Middleton, 2006: p. 15).Slide 2 This is a paradigm that has also been shown to be true in both the European classical tradition and music of many other world cultures (For example the Tala in Indian classical music, reflects the cycle of reincarnation of the Hindu religion, or the Montuno piano rhythms of Cuba, both incorporate repetitive compositional devices). Indeed repetition in Western music has a long standing practice when viewed from both macro and micro perspectives, terminology that Middleton described as discursive and musematic respectively (Middleton, 2006: p. 16).For example, the Sonata Form as employed by Classical period composers[1] pervasively employs repetition on a micro and macro level, with the repetition of the initial ‘exposition’ by the ‘recapitulation’ representing an excellent example of the latter. Slide 3 As outlined by Douglas Webster (1950), most sonata forms are seen to incorporate the mathematical purity of the Golden Section, a paradigm that is not only common in music, but also architecture, painting, and nature. Slide 4 These repetitions usually occur on an inter compositional basis, but as evidenced by the indicative examples of Monteverdi[2] and Prokofiev’s[3] reuse of their own ideas between compositions, and more plagaristic repetitions such as the song ‘Stranger in Paradise’s’ similarity to Boridin’s ‘Gliding Dance Of The Maidens’,[4] can also work on intra compositional levels, resulting in intra-textual allusions, something which ironically has a strong resonance with Adorno’s theory of ‘Standardization’.Slide 5. This paper intends to examine the creative incorporation of a specific type of repetition in popular music, that of loop-based composition (and to a lesser extent improvisation). After presenting a definition of our conception of a loop, our discussion will progress to present an initial typology of the ways in which loops are used in music, in both conventional performance environments, and more explicitly with the aid of technology. This will be followed by a brief overview of the history of tape and digital based looping, followed by an examination of the means through which technological looping can be conceptualised in modern day practices, with a particular emphasis on immediacy and hypermediacy.

What Is a Loop In Music? Slide 6

The terminology ‘loop’ can be seen to be used in numerous disciplines such as science and technology (for example an electric circuit), Mathematics (for example loop algebra and graph theory), computers (for example the ‘infinite loop’), and of course music. The Cambridge Dictionary depicts loops as either a noun (For example the ’Tape Loop’), or a Verb (For example the process of looping), and we would like to spend a short time extending these definitions, with a particular emphasis on music.

Firstly, a couple quotes from authors describing loops as they relate to music technology. Slide 7

“Loops are short sections of tracks (probably between one and four bars in length), which you believe might work being repeated.” A loop is not “any sample, but…specifically a small section of sound that’s repeated continuously.” Contrast with a one-shot sample”. (Duffell 2005, p.14)

“A loop is a sample of a performance that has been edited to repeat seamlessly when the audio file is played end to end” (Hawkins 2004, p. 10).

When describing one of his early experiments with Frippertronics, Robert Fripp described the following process. We take up the story with Fripp entering notes into his duel tape recorder setup throughout the morning, listening to the emotional impact of the repetitions. He stated

“About five minutes later I stumbled over and punched in a few more tones, which turned out to be not the ones I wanted, but I let them stand. This “music” went on and on and on, through breakfast and watering the plants and the rest of it, and by half an hour later the sound had come to seem endowed with a shimmering depth of significance” (Tamm p. 46).

This is congruent to Fripp’s colleague, Brian Eno’s opinion that “Almost any arbitrary collision of events listened to enough times comes to seem very meaningful”, (Eno 1983, 56), and it is this juxtaposition of continuous repetition and consequent ‘significance’ that this paper attempts to negotiate.

This practice is particularly prevalent in mainstream popular musics and more contemporary forms of ‘classical’ music, not only on a melodic basis, but also via a variety of textural constructions we will highlight below. These examples range from compositions that exclusively rely on loops for their entire duration and instrumental strands, to others which selectively incorporate them for specific sections. We would like to propose at this point that many compositions incorporate a number of techniques both diachronically and synchronically, something that will be alluded to as our paper progresses. It is important to note that some of these processes are similar to the theory of Organicism – where a musical work is conceptualised as an ‘Organism’, where individual parts combine to form part of a functioning whole, with the body acting as a metaphor for the musical work. This concept has its roots in the work of philosopher George Hegel (1770 – 1831), who stated that ‘if the work is a genuine work of art, the more exact the detail the greater the unity of the whole’ (Hurry and Day 1982: 341), and this paper intends to extrapolate the means through which this absolutist ‘detail’ can be elaborated upon, and linked empirically to the experience of those involved in making and listening to the music.

What follows is an initial attempt at a typology of loops, as they pertain to music, where in addition to widely known looping techniques such as ostinati and riff, we attempt to develop an extended list of loop descriptions. In order to comply with the absolutist and empirical extremes of the epistemological continuum, we also attempt to align formalist and extra musical ‘qualities’ to these descriptions.

Brief History of Technology for Looping

In appreciating the various compositional applications of repetition it is perhaps only logical that composers should look to new technologies to assist with this fundamental musical process of creating structure through continuously repeating sonic motifs. Historically, this has led to the emergence of novel and often experimental devices, the new techniques that are afforded and even the vocabulary by which these new techniques and sounds can be described. In a more contemporary perspective, these, perhaps, home built solutions have paved the way for a mainstream realisation of similar concepts but available in forms that now suit mass consumption. Perhaps now regarded as the norm in popular music composition, pattern-based approaches for creating and sustaining new repetitive ideas are evident in many, if not most, common software production tools. Patterns and loops can now be layered to create complex sonic experiences with such immediacy that ideas can be developed or abandoned with ease. In considering the state-of-the-art and fully appreciating the opportunities that are now available, it is worth first reflecting on the various historical developments that have occurred along the way.

Locked groove recordings

The earliest examples of technology-enabled audio-loops are generally attributed to the experimental musical works of French composer Pierre Schaeffer. Regarded as the founding figure behind the Music Concrète movement, Schaeffer employed acetate disc recordings to capture real or ‘concrete’ sounds which were manipulated and layered to create rich sonic landscapes. One technique that Schaeffer employed was to interrupt the spiral groove on a recording to create a ‘closed’ or ‘locked’ groove Slide 1. Unlike the terminating locked-groove that prevented the stylus from progressing onto the label, Schaeffer’s closed loops contained recorded sound and were also situated at strategic distances on the surface to offer different loop lengths. Clear examples of this technique can be heard within his 1948 collection of etudes “Cinq études de bruits” and perhaps most notable within these works is “Etude aux chemins de fer” where various sounds from trains are looped to create mechanical rhythmic patterns. Although locked-grooves of this type were superseded by the possibilities offered by the emergence of magnetic tape, the concept remained in use as a novel ‘ending’ to many commercial recordings by bands and artists on vinyl recordings from the 1960s onwards. At the end of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album (1967), the closed-groove is used to store random layered voices and the final groove of King Crimson’s “USA” (1975) produces a cycling loop of applause. More recently, Stereolab’s final track from “Transient random noise bursts with announcements” (1993) enters into a terminal loop at its close with the clue being in the track’s title “Lock Groove Lullaby” and the Super Furry Animals multi-disc album “Rings around the world” (2001) features a side containing a single closed-groove in the middle of the disc; the groove plays a timed sample of the basic groove from “All the shit U do”, a track not featured on the album.

Magnetic tape

Though the concept of looped audio-recordings clearly originates from the early experiments of Schaeffer and his contemporaries, it is not clear whether the term ‘loop’ as used in a sonic context emerged at this same time. It is more likely that the term was first used in reference to tape-loops and even then it is not clear who first coined the phrase or indeed who first explored the transition of the idea from acetate to magnetic tape. Slide 2 During the early 1950s, experimental composers Louis and Bebe Barron were using tape loops in their works and Bebe Barron has suggested that she may well have been the originator of both the phrase and the concept as she knew of no one else who had done similar before then. Yet, it is also clear that Les Paul was experimenting with tape-loops in his guitar works at a similar time and also that Pierre Schaeffer’s interest in sonic loops moved into the use of magnetic tape and ultimately to the commission of a device called the Morphophone Slide 3. Created by Fances Poullin in the 1950s for Schaeffer, this device featured a revolving cylinder of 50cm with a loop of magnetic tape around it. Armed with twelve heads (record, erase and then ten moveable heads for playback) a short recording could be cycled around indefinitely with different timed delays being offered by the spacing of the playback heads (Teruggi 2007). Two paths perhaps emerged at this point, one that moved towards the use of closed loops of magnetic tape to produce prolonged echo delays as commercialised within products like the Echoplex (c. 1959) Slide 4 and one that moved towards the use of closed-loops to accumulate layers. Though the use of tape-delay is of interest within the scope of this presentation, it is perhaps the latter use of magnetic tape, to emulate the closed-groove concept whilst offering the potential to introduce further layers that is of more immediate interest.

The most notable early explorer of tape-layering using loops in this way is Terry Riley. Prominent as an experimental composer and performer within the emerging minimalist music movement of the early 60s, Riley conceived a structural idea based on long loops of sound, being layered and adapted over substantial periods of time. Using two reel-to-reel tape recorders, Riley developed the “time lag-accumulator” for this very purpose using the device to create huge live performances, creating loops whilst simultaneously improvising over them. His pieces “Reed Streams” 1966 and “Rainbow in Curved Air” 1969 are indicative of the live performances that Rile was achieving at the time. Slide 5 A more mainstream application of the same technique was offered by Robert Fripp and Brian Eno in their 1973 collaboration on “No Pussyfooting” with Fripp subsequently coining the term ‘Frippertronics’ for his interpretation of Riley’s original device.

Digital Audio

Originally conceived as digital counterparts to the earlier tape-based echo machines (Echoplex c. 1959 and WEM Copicat c. 1958), early digital delay pedals such as the Boss DD2 (c. 1984) offered perhaps only a few seconds of delay time but if feedback was set to a high level, this could effectively be turned into a closed-loop effect. In this respect, digital delay pedals could offer similar capabilities for layering to those explored by the likes of Riley and Fripp but working with much shorter loops. The first dedicated digital loop-recorder was the Paradis Loop Delay (c. 1992), a device where the functionality reflected the use of continuous loops more than it did the use of gradually diminishing echo-like delay. As with the division of paths in the evolution of analogue approaches to delay devices and loops devices, similar is true within the digital domain seeing FX approaches to delay developing in parallel to sustained structural development of continuous loops. The latter leading to the development of dedicated ‘loop stations’.

Analogue Step Sequencers

Although the development of digital approaches for storing and manipulating audio new possibilities were quickly realised for taking the potential for working with loops to new levels it is important to acknowledge the evolution of another approach to loop-like generation of patterns in electronic music that was progressing in parallel around this same time.

Companies producing modular synthesisers in the 1960s began to offer modules that would allow a series of control voltages (CVs) to be cycled in a seemingly endless loop. Slide 6 In the most basic of formats, modules such as the Moog 960 step sequencer could send these CVs to produce, for example, a series of pitched notes, the sequencer would then cycle through this tone-row by a speed set by clock circuit. Although seemingly basic in terms of melodic development, a step-sequencer of this sort was a highly effective method of creating and controlling ostinato patterns. A technique that was used extensively by, for example, Tangerine Dream became a common feature of less modular, dedicated synthesisers of the type favoured by the electronic bands of the early 1980s who continued to use the step-sequencer as a generator for laying down ostinato grooves (for example “Dreams of Leaving” by The Human League 1980). Though more flexible approaches to sequencing (particularly using the MIDI protocol) have emerged in the decades that have followed, it is interesting to note that the concept of step-sequenced loops and/or repeated patterns has remained, frequently being presented as a fundamental building block for composition.

Phrase samplers and hybrid devices

The contemporary music composition and production suite is likely to incorporate software environments of the types just mentioned, platforms for fast creation and manipulation of looped phrases along with looped digital audio. These have become the established norm for much of the recorded commercial music that is being produced for today’s market. Yet, the experimental interest in loops remains (Add N to (X), Aphex Twin, Mùm) as does the desire by performers to improvise with looped material (Son of Dave, Imogen Heap) and so the technological development of hardware and software tools for loop-based performance continues. Slide 7 Most recently, the Korg Kaos series, is offering hybrid devices for recording multiple loops and manipulating them in realtime (Kaospad) or for generating and synthesised phrases and recorded loops to similar effect (Kaossilator).

Discuss the Model

Conclusions Slide 8

As noted by academics such as McClary,[5] Auslander[6] and Zac[7] electronic modes of production often aim to precipitate ‘immediacy’ in the listener, becoming noticeable only when closely scrutinizing the text. This is congruent to the proposition presented by Bolter and Grusin (1999), who argued that modern society is driven by a desire for realism, a need which is met by a variety of new media forms ranging from spacial innovations like stereo, quadraphonic and three dimensional movies, to the improved digital quality of compact disks and high definition TV. According to Bolter and Grusin, the irony of this process is that in the quest for realism, the technology making this possible is often foregrounded, resulting in a process they entitle ‘Hypermediacy’, where the audience is reminded of the technological medium, resulting in an increased awareness of ‘seeing’ (or in our case hearing). When considering the work of loop based musicians such as Robert Fripp, David Torn and Bill Frisell, who use technology as a means of generating loops during live performance, from an audience perspective they can be seen to often straddle the divide between the immediacy of more conventional performance and a process we describe as Non Realistic Hypermediacy, where the technology is perceived not as a means of generating realism, but as a means of creating sounds and textures that often appear to be beyond the scope of what audiences can perceive – the impossible made real!. For example, when examining a live performance by vocalist Amy X Neuburg:[8] Play Slide/Video We propose that the combination of the voice, the signal processers, and the resultant sound arguably ‘encourages’ the listener to consider how the link between the instrument and the timbres are generated. How can a single performer generate these sounds, and why do they not sound like a single performer? Susan McClary’s observation that ‘the closer we get to the source, the more distant becomes the imagined ideal of unmediated presence’[9] is noteworthy on this occasion, as it could be argued that performances such as this display the reality of what is hidden in much commercial pop music – the incorporation of technology. Additionally, McClary’s observation also provides an interesting addition to Hagel’s Organicism outlined earlier, with both philosophies indicating that the detail of the individual parts reflect the ‘truth’ of the whole. In Organicism’s case the interrelation of the parts are primary, in McClary’s it is the means through which the sounds are achieved. It is proposed that when analysing loop based compositions generated via sound processors, it is important to focus on not only the formalistic melodic, harmonic and rhythmic conventions of western music, but also on factors such as the impact of the mediated voice on the performer’s creative decision making (This is also the case for the listener, but this is beyond the scope of this discussion). This raises a number of important questions such as: how does the performer creatively engage with a machine from an improvisational and compositional perspective?[10] How are specific sounds and textures produced? What are the impacts of these processes on notions of authenticity? How does the listener make sense of what appears on the surface to be disjuncture between performer and sound, input and output? How and why do listeners make meaning out of what can initially be a series of random events? [11] What impact does the juxtaposition of live and recorded elements have on both creativity and reception? What are the textual allusions when looping overlaps with sampling other composers work? And finally, what are the impacts surrounding the minimalist mantra – ‘repetition as a form of change’?,[12] and how does this resonate with Roland Barthes’ view that ‘The bastard form of mass culture is a humiliated repetition’. He continued ‘always new books, new programmes, new films, news items, but always the same meaning’ (Barthes 1975: 24).

Although there is not time to answer these questions now, this is something we intend to explore in the next stage of this research, and welcome any feedback anyone has to offer.

Thank You Final Slide

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland, The Pleasure of the Text (Hill and Wang, 1975).

Bennett, Andy, Barry Shank, and Jason Toynbee, The Popular Music Studies Reader (Routledge, 2006).

Teruggi, Daniel (2007). “Technology and Musique Concrete: The Technical Developments of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales and Their Implication in Musical Composition”. Organised Sound 12, no. 3:213–31.

Holmes, T. (2002) Electronic and Experimental Music. Routledge, GB

Duffell, Daniel (2005). Making Music with Samples : Tips, Techniques, and 600+ Ready-to-Use Samples. San Francisco: Backbeat. ISBN 0-87930-839-7.

Hawkins, Erik (2004). The Complete Guide to Remixing: Produce Professional Dance-Floor Hits on Your Home Computer. Boston: Berklee Press. ISBN 0-87639-044-0.

[1] between around 1759 – 1830

[2] Who incorporated material from L’Orfeo in the 1610 Vespers.

[3] Whose 3rd Symphony is heavily influenced by his opera Fiery Angel.

[4] From Polovtsian Dances.

[5] Andy Bennett, Barry Shank, and Jason Toynbee, The popular music studies reader (Routledge, 2006), p23.

[6] Philip Auslander, Liveness (Routledge, 2008), p76.

[7] Albin Zak, The poetics of rock (University of California Press, 2001), p47.

[9] Sheila Whiteley, Andy Bennett, and Stan Hawkins, Music, space and place (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005), p167.

[10] It could be argued that looping technology negates the need to communicate with other musicians.

[11] Does the loop have the impact of magnifying the initial event?

[12] For example although a loop may repeat exactly, the time and circumstances surrounding it will differ.