Well, I am hopefully now in the final stage of the editing process for my Sting book. The (hopefully) final draft is sent off – so I am getting ready to enter the process of indexing and finalising the final photos that will be used. So, one of the bits I have deleted from my first draft is a description of each chapter – so here they are here. Here’s hoping the real thing will be out soon.

The book explores Sting’s relationship to place and space via the themes of the following chapters.

Chapter 1 commences by outlining Sting’s background in Newcastle. The chapter provides a historical context to Sting’s place of birth, its Roman past, Swan Hunter shipyard, the coal mining industry, the tension of working class and middle class values, and his Catholic upbringing – all of which are so important when attempting to understand Sting’s identity, sense of place and subsequent creative output.

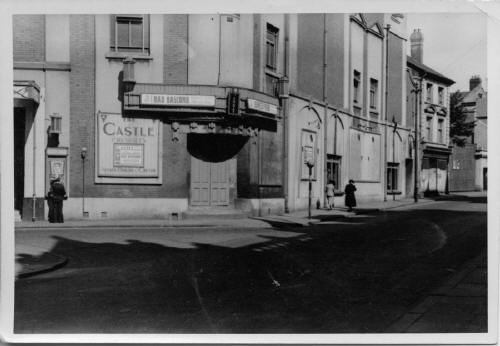

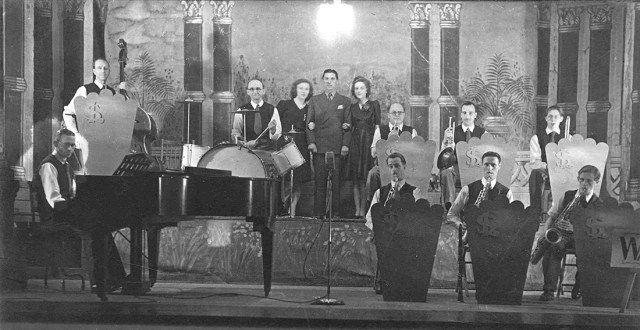

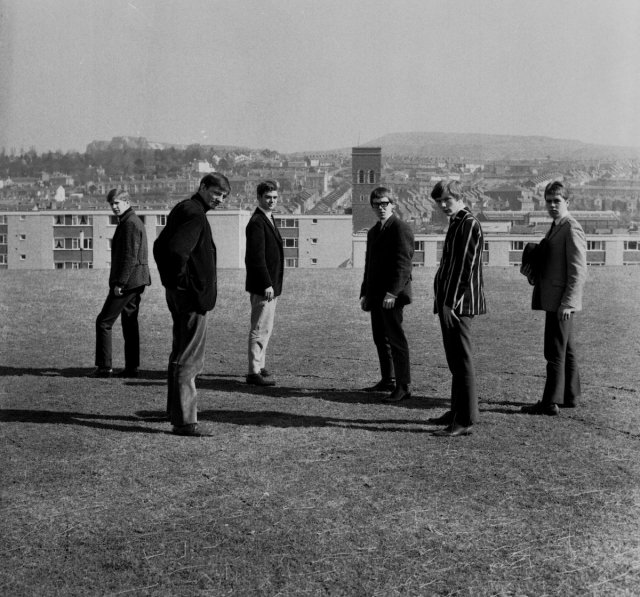

Chapter 2 focuses upon the specifics of the relationship of Sting’s hometown in the construction of his identity. After outlining some of the meanings associated with the word ‘Geordie’, the chapter considers Sting’s current complex relationship with his hometown, and some of the songs that have expressed this. The chapter also considers the ways in which Sting’s relationship with ‘home’ has also helped him circumnavigate two instances of writer’s block and how his songs are arguably feeding into the redefinition of what it means to be a Geordie. Most importantly, the chapter suggests some of the reasons why an artist such as Sting finds it necessary to construct more than a single identity, and how ‘stardom’ has impacted upon this necessity.

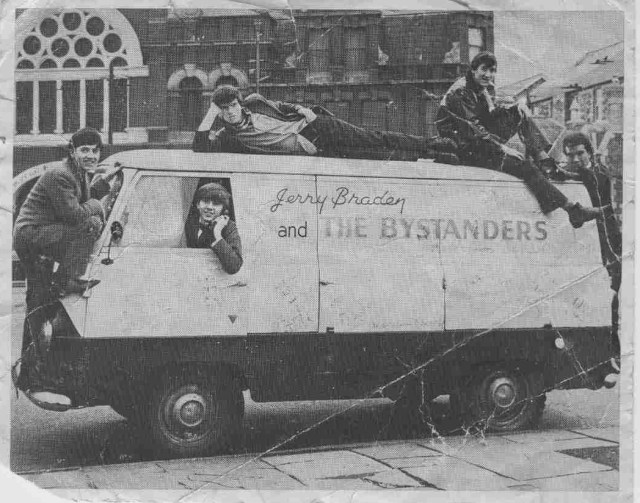

Chapter 3 discusses Sting’s time in Newcastle with his first band – Last Exit. Rather than write a chronological account of the history of the band, it was decided to interview a range of people who were involved with Sting during his time as a local musician based in the North East of England. The chapter considers his early influences, the venues he frequented, and his early performances, in addition to providing an account of Sting’s early role as a freelance musician and his dealings with musical theatre, providing an important lineage to his work on The Last Ship.

Chapter 4 commences with a brief case study of the now demolished Impulse Sound Recording in Sting’s hometown of Wallsend – the place where Sting recorded his first recordings with the Phoenix Jazzmen and, more importantly, many of the demo recordings with Last Exit. After briefly discussing the history of the studio and its location, the chapter proceeds to allow the people who actually worked with Sting to describe the idiosyncratic traits of the studio and the development of Sting as an artist, whose early vocal and songwriting abilities were developed in this space. The discussion then highlights 29 individual Last Exit compositions/recordings produced in the two-year period they were together, fifteen of which were composed by Sting. After discussing the available recordings more generally, the chapter proceeds to examine early demos of five songs that progressed onto international acclaim with The Police and Sting’s solo career, with a particular focus on the changes Sting implemented when performing the songs in a new commercial environment.

Chapter 5 focuses on Sting’s move to London and the eventual formation of The Police. After leaving Newcastle in January 1977, the chapter discusses the early London performances Sting undertook with Last Exit, his early rehearsals with Stewart Copeland, and how he resonated musically and philosophically with the punk scene and cultural backdrop of London. The chapter includes details of the early tours by The Police, and includes interviews with ‘Fall Out’ photographer Lawrence Impey, music promoter Jonny Perkins and one of the first musicians he worked with after moving to London, ex Gong bass player Mike Howlett, who actually introduced Sting to Andy Summers and played in an early incarnation of The Police – Stontium 90.

Chapter 6 initially focuses on the early accommodations Sting occupied in London, particularly highlighting the basement flat he settled in at 28 Leinster Square in Bayswater in the early months of 1977. The Chapter continues with a discussion surrounding how a number of seeming coincidences (what Sting would call synchronicity) – such as The Police’s appearance in a Wrigley’s spearmint gum advert in February 1978, Sting’s role in Quadrophenia, a heavy touring schedule and the recording of the first album by The Police, Outlandos d’Amour – eventually resulted in commercial success in the UK in 1979, which included top 20 hits with ‘Roxanne’ and ‘Can’t Stand Losing You’, in addition to a headline appearance at the Reading Festival on 29th August 1979. There is also a discussion surrounding his compositional working methods, which are often conducted in ‘places of convenience’, such as the flat in Bayswater, his car, the recording studio and on the road – often with the use of portable recording technology to document his ideas. The chapter then examines Sting’s songwriting, which is seen to derive from fragmented extracts, sometimes with the aid of notetaking and music technology. He is also noted as considering the instrumental music itself to have its own narrative, which is then often juxtapositioned against often contradictory lyrical content. The chapter concludes by proposing a number of reasons why Sting has made creative decisions, where he thinks his inspiration comes from, and ways in which he has circumnavigated writer’s block.

Chapter 7 considers Sting’s emergence as a writer of political songs in the early 1980s. Commencing with his engagement in live events such as the ‘The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball’ (1979), Live Aid (1985), the ‘Participation of Hope Tour’ (1986) and the Human Rights Now! Concerts (1988), the chapter considers how Sting emerges as an independent star presence, travelling the world with an aim not only to raise funds, but awareness of human rights issues. His involvement in the 1988 Human Rights Now! Concerts witness him travelling to Third World countries such as New Delhi, Zimbabwe and Argentina, with a performance of ‘They Dance Alone (Cueca Solo)’ at River Plate Stadium, Buenos Aires, being a particularly poignant event. Originally recorded on …Nothing Like The Sun, the song was inspired by the women who perform the traditional Chilean courting dance (the Cueca) alone, with pictures of their dead husbands, fathers and sons pinned to their chest. An overt protest to Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet (1915 – 2006), the location of the concert is interesting, as it is located in a country where many Chilians fled to during the Pinochet regime – as it was not possible for Sting to perform in Chile in 1988 for political reasons. Two years later, in 1990, the song was performed at the National Stadium in Santiago, Chile, providing a fabulous example of the power of the combined forces of music and place. The discussion then focuses on the criticism Sting has received for his political activism in the UK press, examining how, despite good intentions, his activities often seem to result in negative press. We see Sting described as a do-gooder and a bore, with the press even depicting his activities with the Rainforest Foundation as a “self-aggrandising global photo-opportunity”.[i] This press coverage can be seen to come from all directions, including The Daily Mail, The Guardian, The Sunday Times, The Daily Mirror and The Independent, with many taking the opportunity to criticise his fund raising even when reviewing his music – effectively confusing the two activities. Placing Sting’s music in context alongside other artists who have incorporated indigenous, often non western influences and sounds in their music and re-appropriated them for their own artistic ends, the chapter asks the question: do songs such as ‘They Dance Alone (Cueca Solo)’ and ‘Desert Rose’ de-contextualise the music and traditions of oppressed countries, or do they, as Sting intended, raise awareness of oppressed people and artists who otherwise have limited commercial success?

The final chapter of the book initially focuses on Sting’s touring schedule in both The Police and his solo career, and how the symbiotic relationship of both America and the UK fuelled his success. After briefly discussing the early tours and singles of The Police, the chapter proceeds to consider the emergence of The Police as an ‘authentic’ band, after initially causing confusion with the music press on both sides of the Atlantic in terms of their punk credentials. More specifically, the chapter explores how the music press at the time made sense of Sting as a songwriter and performer, and how he gradually emerged as a creative force, taking over from Stewart Copeland as the spokesperson of The Police. The chapter concludes by considering why Sting has been given such a hard time by the press when disguising his background, making comparisons with other artists who have undertaken a similar process. The chapter also considers arguably his most nostalgic gesture, The Last Ship, which in many respects has assisted the process of him coming to terms with his past and making peace with his hometown.

[i] Alan Jackson ‘Change The Record Sting’, http://search.proquest.com.ergo.glam.ac.uk, The Times, 30th January1993.

This paper combines fragments of two forthcoming journal articles on Robert Wyatt’s Matching Mole. After providing a brief analysis of selected tracks from the band’s two official albums, the paper will consider how their creative output resonates with genre, stylistic labelling and protest narratives. This short-lived band were formed during the last couple of months of 1971, after Robert Wyatt had completed his five-year tenure in Soft Machine, with the name simply being a sarcastic pun on the French translation of his old band – Machine Molle. In addition to Wyatt, the band consisted of Phil Miller on guitar, Dave Sinclair and Dave MacRea on keys and Bill MacCormick on bass. I had the opportunity to interview three of the five members when putting together this paper.

This paper combines fragments of two forthcoming journal articles on Robert Wyatt’s Matching Mole. After providing a brief analysis of selected tracks from the band’s two official albums, the paper will consider how their creative output resonates with genre, stylistic labelling and protest narratives. This short-lived band were formed during the last couple of months of 1971, after Robert Wyatt had completed his five-year tenure in Soft Machine, with the name simply being a sarcastic pun on the French translation of his old band – Machine Molle. In addition to Wyatt, the band consisted of Phil Miller on guitar, Dave Sinclair and Dave MacRea on keys and Bill MacCormick on bass. I had the opportunity to interview three of the five members when putting together this paper.

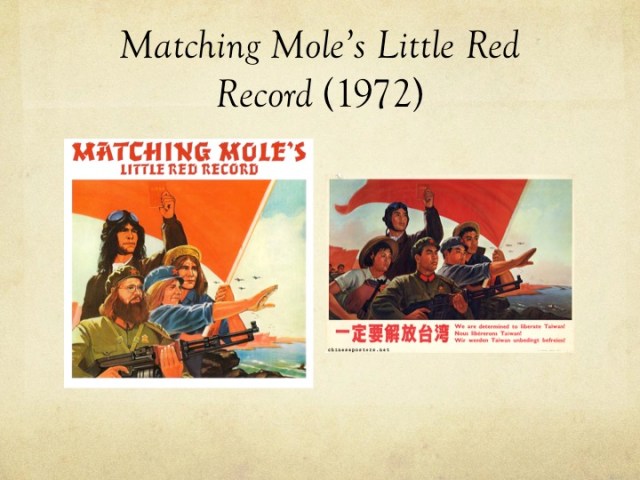

to a House of Commons episode in November 2015, when the Shadow Chancellor John MacDonell was heavily criticised for jokingly quoting Zedong when attempting to make a point about the UK government selling off state assets to the Chinese.

to a House of Commons episode in November 2015, when the Shadow Chancellor John MacDonell was heavily criticised for jokingly quoting Zedong when attempting to make a point about the UK government selling off state assets to the Chinese.